A BRITISH EVENING OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND ELGAR

Ariel Barnes, cello: VSO/ Bramwell Tovey, Music of Walton, Butterworth, Elgar and Vaughan Williams, Orpheum, October 4, 2014.

This Vancouver Symphony concert was seemingly in the same spirit as Prom 72 with the BBC Symphony that took place a few weeks ago, both having Vaughan Williams’ magnificent Fourth Symphony (1934) as their centerpiece. Performing this powerful work of course has become somewhat commonplace in the UK. Here it was certainly more of an occasion since the work has not had a performance for at least 30 years! Also featured was the solo debut of the VSO’s recently-appointed principal cellist, Ariel Barnes – in the Elgar concerto -- as well as shorter works by Walton and Butterworth.

Vaughan Williams’ Fourth is so vastly different from its symphonic predecessors that it has found a natural classification as the first of the composer’s great triad of ‘war symphonies.’ This is in spite of the fact that the composer himself denied any war inspiration, calling the work just ‘absolute music’. Nonetheless, one can be easily confused by the composer’s comments if one listens to his benchmark (1937) recording -- unequalled for its fire, fury and anger. Surely there must be something earth shaking going on here! Over a year ago, I did manage to see a performance by conductor/ composer Ryan Wigglesworth and the London Philharmonic that was a pretty extreme attempt to remove programmatic allusions and present the symphony simply as “one with a lot of interesting counterpoint”, to cite the conductor. But, while fast and brilliant, this interpretation struck me as cold and uninvolving.

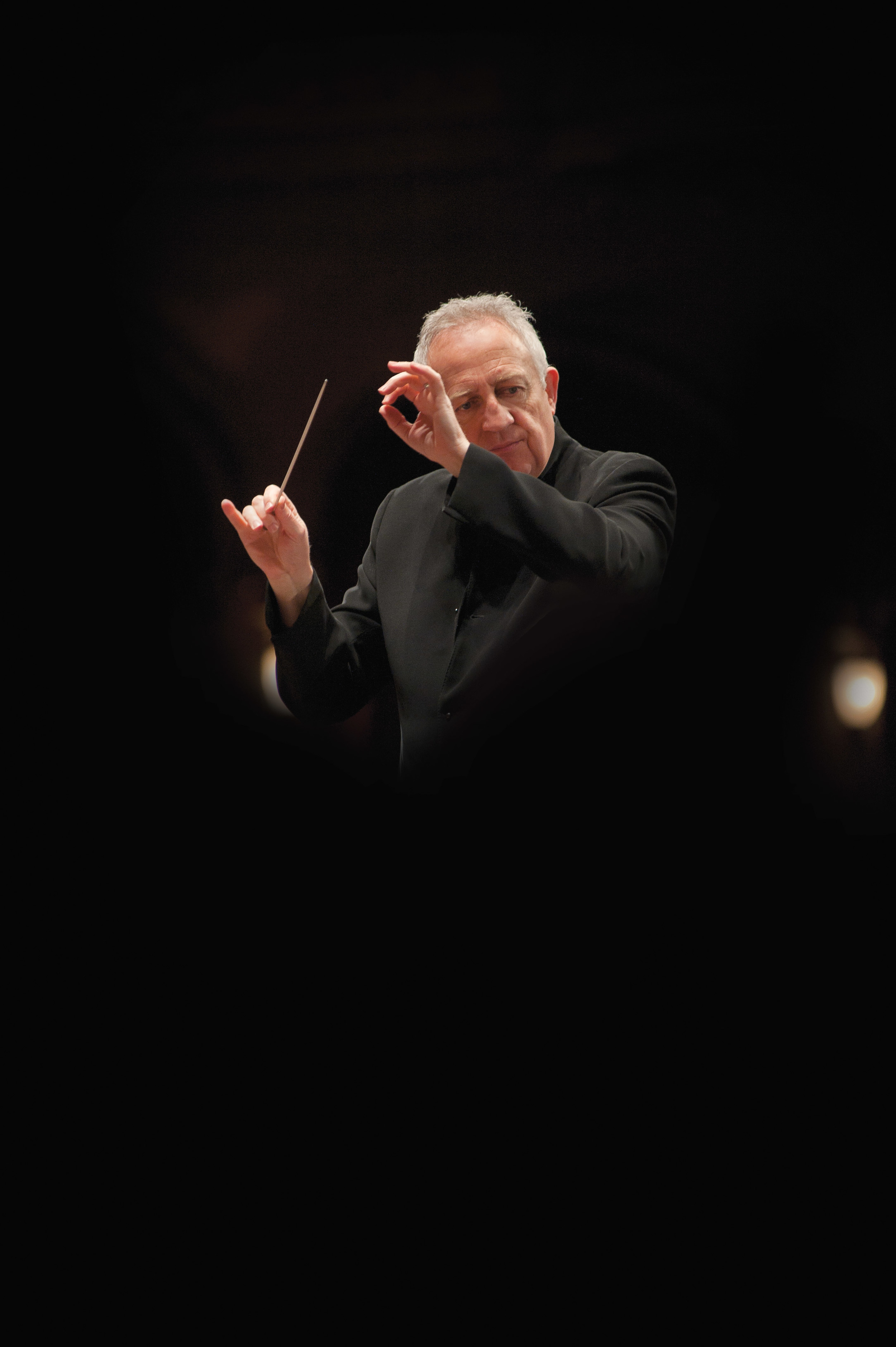

Maestro Bramwell Tovey obviously feels this work deeply, its elemental power, its dignity, and its bleakness, and he coaxed a very convincing response out of the orchestra. Tempos were moderate but not much slower than the Boult/ Handley tradition that we are used to. The variety of brass work was negotiated well, although at times I felt that this section could be even sharper and more pungent. And the strings showed strength and resiliency. The first movement had breadth and coherence, contrasting its brazen punctuations successfully with its quieter, enigmatic underpinnings. The latter took over more strongly in the following movement, the conductor providing sinew at first but then allowing a steady and concentrated descent into a more bleak and removed landscape. Some of the pungency of the wind playing and string shaping actually took me to the icy terrains of the Sibelius Fourth Symphony, and I certainly had not felt that before! The remarkable Scherzo, where the music almost turns back against itself, provided just the right contrast, although here execution might have been more exact. Then, the great transition to the Finale (a parallel to the transition in Beethoven’s Fifth), here louder and faster than usual, almost pushing us into the passion of the last movement and in turn transporting us through the movement’s many varied protestations to its famous closing timpani ‘thud’. The conception was really first rate. Not as craggy and uncompromising as some, but wonderfully purposive and full of conviction. Certainly, no one would leave this concert thinking that this work was anything other than a masterpiece.

The other significant item at this concert was cellist Ariel Barnes’ solo debut in the Elgar concerto. Sometimes I do wonder whether this is a concerto that should be played early on in one’s career. It is not a standard romantic cello concerto, yet there is a temptation to treat it as such. I have often seen young cellists try to place more expressive fervour into this work than its eloquent, refined foundations really allow. At the same time, they often fail to be sensitive enough in all the lovely, quiet passages of intimate musing. That was true to some extent here. Ariel Barnes has an enviably rich and strong tone and obvious agility, and achieved considerable beauty at many points. But it frequently took the cellist a while to scale his expression exactly to the music. Thus, his opening was slightly too weighty and fulsome, impeding rhapsodic flow and flexibility as the movement progressed. The feeling both at the end of the heartfelt Adagio and at the end of the finale ended up almost exactly right but it seemed to take too long to get this in place. Perhaps the Adagio worked best, with both the first and last movements only a qualified success from the standpoint of both soloist and orchestra. The first had a few too many tepid moments with the orchestra sometimes inflated; the jaunty pace for most of the last movement also did not seem right, especially with a speeding up towards the end. In the finale, the cellist needed to find more composure as well as refinement in tone and shading. Overall, a creditable journey for this young and talented cellist but still unmistakably a work in progress.

Walton’s Façade Suite No. 2 and Butterworth’s Banks of Green Willow opened the concert in engaging fashion. But it was the Vaughan Williams that was the real story here.

© Geoffrey Newman 2014